By Lena Karamanidou (Glasgow Caledonian University) and Bernd Kasparek (Georg-August Universität Göttingen).

2018-11-08

On our way from Orestiada to Alexandroupoli – the two largest urban centres in the border region of Evros, Greece – a young migrant, holding some Euro notes in his hand, tried to board the public bus we were travelling on. The conductor refused him: ‘Police. Papers. Then travel!’, he said in English. He acted within the confines of the European and Greek law: providing transport to an undocumented migrant is considered facilitation – helping a person with no legal status to enter or transit through a country – and carries heavy fines.

The previous day, one of our respondents told us that when migrants try to make their way towards the cities of Thessaloniki or Athens after leaving the Fylakio Reception and Identification Centre (RIC) or are released from detention, most have to pay their own fares. Previously, EU funding for Greece went through the UNHCR, and the UNHCR would use the funds to provide transportation to Thessaloniki. But since the funding is now going through the Greek state, no more transport is provided. Yet, as migrants normally cannot prove they are in Greece legally, they might be apprehended by the police on the way inland, re-arrested or just removed from the bus. Then they have to pay fares again.

This incident – however undramatic compared to other developments in Evros – encapsulated the interconnected nature of the European border management framework and domestic controls, and their failures. It also pointed to how actors on the ground can affect its implementation. The conductor did not call the police – at least not while we were on the bus.

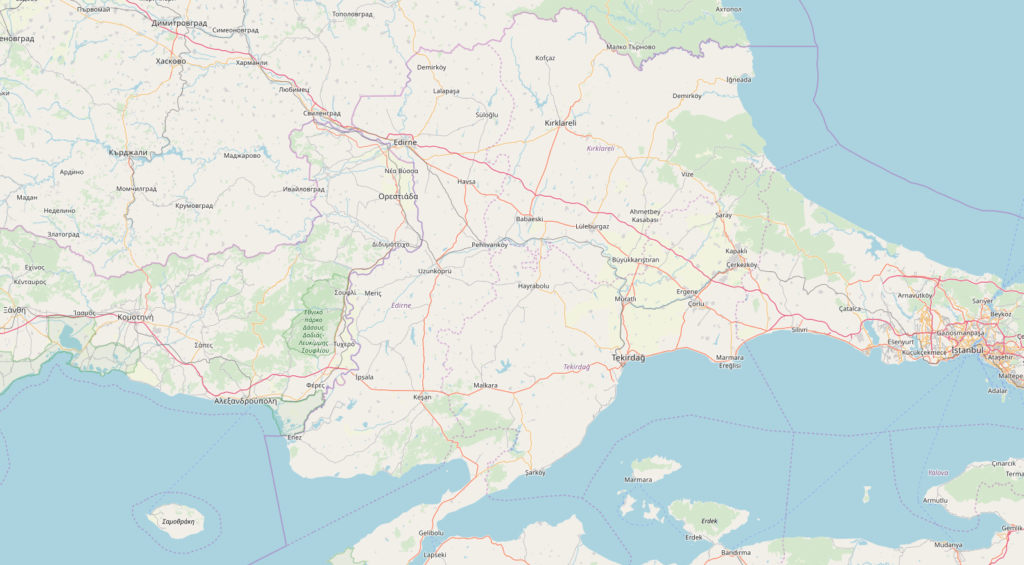

The region of Evros. © OpenStreetMap contributors

Our visit to Evros – the north-eastern area of Greece that forms the only land border with Turkey, most of which is constituted by the river Evros (Maritza in Bulgarian, Meriç in Turkish) – happened almost by chance. We were invited to a workshop in Istanbul and given the proximity of the two locations, a four to five-hour coach trip away, we decided to seize the opportunity and conduct fieldwork. We had recently finished the project report on EU Border management and migration control, and Evros provided an opportunity to study in situ if and how the EU legal regime works in practice, and our interest in the country and the area is long-standing. We have both researched the impact of European legal and policy frameworks on migration and asylum policies in Greece for more than a decade. We both conducted fieldwork in Evros in 2010 and 2011, around the time of the deployment of the Rapid Border Intervention Team (RABIT) by the European Border Agency Frontex in the winter of 2010/11.

Seeing how border management and protection practices have changed since then was of great interest, given the numerous developments at the EU and domestic level. The deployment of the RABIT force, and the continuing involvement of Frontex in border surveillance and management activities – identification, nationality determination and interviewing migrants arriving at Evros. New structures such as the Regional Centres for Integrated Border and Migration Management – with two regional offices in Orestiada and Alexandroupoli – were created to facilitate the implementation of EU border management policies and the cooperation between EU agencies and Greek authorities. The Europeanisation of border management and the cooperation of the Hellenic security agencies and Frontex, according to our Hellenic Police respondents, improved professional practices – such as in nationality determination, screening and debriefing, undertaking risk analysis.

The detention centre in Fylakio, 2010. The later added containers are not in place yet. © wikimedia user:ggia, CC BY-SA 3.0

Europeanised border management practices were also supported by the reform of Greek asylum and reception systems. Fylakio, near Orestiada, was the first First Reception Centre – renamed into Reception and Identification Centre since the 2016 law introduced in response to the EU-Turkey statement – to be established in 2013. Before 2013, it existed as a detention centre for migrants, and has since been expanded by the ubiquitous container architecture characteristic of today’s migration management. While reception points to humanitarian procedures such medical screening, psychological support and vulnerability assessments, activities in Fylakio were also extended to border management activities, consisting of the identification, determination of nationality and fingerprinting of migrants arriving at Evros. While the RIC is based in the containers, the old concrete structure continues to serve as a pre-departure detention centre (PROKEKA) to facilitate detention and the implementation of Greek and EU return policies.

A view of the main square of Orestiada. Photo: Bernd Kasparek

So what has changed in Evros?

Since 2017, crossings through the Evros border have doubled. There were 5,677 arrests of third country nationals in 2017. By the end of September 2018, there were about 12,442 based on the information given to us by the police directorates in Alexandroupoli and Orestiada. The increase in arrivals is partly explained by the rise in the number of Turkish nationals crossing into Greece, in all likelihood fleeing an increasingly oppressive Turkish post-coup regime. There was a peak of arrivals in April and May, but the trend of increased arrivals continues. Interestingly, the number of arrests and detections are at the 2010 levels that triggered the RABIT deployment.

It’s difficult to point to one reason for the increased use of the Evros route. One explanation given by the police related to the low water levels of the Evros river, making crossing easier and safer. But there are many other factors: most importantly, the collapse of cooperation between the Greek and Turkish authorities since 2016. While the Turkish coup was a factor, the arrest of two found without authorisation in Turkish territory marked yet another turning point. According to our respondents, this affected communication between border control authorities and cooperation on returns, which all but broke down. The exclusion of Evros from the EU-Turkey statement and hotspot arrangements is also significant: it makes it a better route for avoiding return to Turkey.

Little attention has been paid to these shifts, as the public focus remains on the Greek islands, the hotspots there, and the implementation of the EU-Turkey statement. However, there is a lot of concern locally. Some of the concerns raised by local residents touched on ‘qualitative’‹ changes: that the migrants arriving are not only Syrian refugees or families, but also other nationalities, single men and ‘criminal elements’ – the latter reflecting hostile representations of migrants in local and national media, but also long-term public discourses criminalising and securitising migration in Greece. There were concerns that a potential military intervention in Idlib, Syria would exacerbate the situation in Evros, while increasing economic and political instability in Turkey might have an impact on movements in the area. Evros, it was said in a dramatic fashion, ‘will blow up’.

Orestiada is located in proximity to both Bulgaria and Turkey. Photo: Bernd Kasparek

A Europeanised border regime?

In a sense, our visit in Evros was a case of déjà vu: some of the deficiencies is asylum and reception widely reported in 2010-2011 still persist. Despite the establishment of the Hellenic Asylum Service in 2013, a local regional office in Alexandroupoli and a mobile asylum unit within Fylakio, the examination of applications is lagging behind. The use of short term contracts for staffing asylum services – a side-effect of the country’s austerity crisis and difficulties in absorbing EU funding – was identified as a significant factor. The reception conditions in Fylakio are reported to be still lower than European standards of reception and detention. There was no doctor in the RIC for nine months and there are shortages in interpretation services. Conditions at the pre-departure detention centre are worse, with insufficient heating, sewage problems and the presence of stray dogs being mentioned both by our respondents and in media accounts. Due to the limited capacity in the RIC, the PROKEKA facility is used as an additional space for screening procedures. This in itself points to different functions than those envisaged in the context of the EU border management regime – facilitating return. The strict separation of concerns which is part and parcel of all EU border and migration management strategems clearly breaks down on the ground.

The Europeanised border control regime also co-exists with a national legal and policy framework for controlling migration. According to Law 3386/2005, unauthorised entry is a criminal offence. Migrants entering Greece in an unauthorised manner are arrested and detained in border police stations, while the police obtain from the local administrative court an order that allows them to refrain from criminal proceedings. This order is normally issued within 48 hours. Only following this, migrants are directed to the Fylakio RIC if they are of a nationality considered to be of ‘refugee profile’ – with a recognition rate of over 75% in the EU. If they are not, they are detained, but then released, since the collapse of Greek-Turkish cooperation has affected the implementation of the Bilateral Readmission Agreement. Since 2014, Operation ASPIDA (Shield) diverted resources to Evros in order to enhance the border control capacities of the Hellenic Police, aiming at the deterrence (apotropi was the word used by one of our police respondents) of migration movements across the border. Some controls seem to have a local flavour. The hotel where we stayed, we were told, keeps two books for recording their guests: one for the hotel itself, and one for the police, who come and check who is staying there every night.

The new highway leading to the border crossing of Kipoi/Ipsala. Photo: Bernd Kasparek

However, the most disturbing practice we heard about was illegal pushbacks. Pushbacks – returning migrants to Turkey and across the Evros river in contravention to both the non-refoulement clause of the Geneva Convention and EU law – have been widely recorded by NGOs in the late 2000s and early 2010s. In 2017 and 2018 Greek and European NGOs documented illegal pushbacks across the Evros river. Based on the information we obtained, this practice continues. According to our informants, after detention in border police stations, migrants are put in vans, taken back to the border, put into boats and led back to Turkey. These accounts reflected testimonies compiled previously by Greek NGOs. While they seem to be conducted by Hellenic Police and Army personnel, it was also indicated to us that Frontex may be involved in this practice, or at least knows and tolerates it. However, we were not able to independently corroborate this.

The practice of pushbacks is both illegal and inhumane: it endangers people’s lives and prevents them from reaching the protection regime of the European Union. Local people defending migrants’ rights pointed to the lack of media interest, domestic or global. Unlike the incident of the three murdered women which occurred while we were in Orestiada, the pushbacks do not seem newsworthy. They are difficult to record or investigate: they take place in secret, at night, with small groups of migrants each time. Yet, the Europeanised border regime fails to account for localised border practices that violate the human rights norms it purports to respect.