By Monika Szulecka (Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw), Marta Pachocka (Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw) and Karolina Sobczak-Szelc (Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw)

The development of Poland’s migration and asylum policies and laws date back to 1989 when political and socio-economic transformations began. At this time, the whole region of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) experienced important changes, ranging from the collapse of the Soviet Union (USSR) and the establishment of new states and governments to the economic development and progressive integration of some post-communist states within Western Europe. The geopolitical changes in the region brought an ‘opening’ of borders in Poland. Waiving restrictions in passport policy contributed to increasing mobility both from and to Poland. Importantly, Poland as a country between the East and the West also became a transit country for economic migrants and asylum seekers. The attractiveness of Poland as a country of destination increased along with its accession to the European Union and joining the Schengen zone. And, the EU accession contributed significantly to the outflow of Polish nationals to the EU labour markets. At the same time, however, it also influenced the development of migration policies and laws, which became necessary not only to react to observed phenomena (a reactive policy characterised the 1990s in particular), but also to manage external migration to be the most profitable to the country and its economy while attracting desirable migrant workers to the Polish labour market.

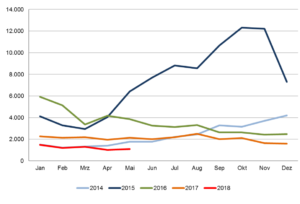

The history of asylum seekers and refugees in Poland is strictly determined by the region of origin of foreigners seeking protection in Poland. For more than two decades, foreigners applying for a refugee status at the Polish-Belarusian border (usually at railway BCP in Brest/Terespol) have been mostly from the Caucasus region (formally Russian territory). The migration and refugee crisis experienced by Europe in 2015 and in the following years did not influence the demographics of arriving migrants and asylum seekers in Poland. These were rather conflicts or political and economic disturbances in countries to the east of Poland that shaped the demographics of asylum seekers and foreigners granted international protection. The consequences of the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ or problems encountered by countries in the Middle East were to some extent reflected in Poland’s experiences of admitting asylum seekers. One example is the very high rate of recognition of applications for international protection submitted by citizens of Syria. However, asylum proceedings linked to inflows from the Middle East did not dominate in terms of the overall administration of asylum applications submitted in Poland.

Since 2015, new intensive debates about possible solutions to the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ have prompted Polish policy-makers to introduce reforms to both international protection and immigration law. With arguments pointing to the need of avoiding problems with admitting asylum seekers and conflicts related to differences in culture and religion, the new Polish government of October 2015 has been refusing to implement both relocation and resettlement schemes proposed by the European Commission within the framework of the European Agenda on Migration (EAM) issued in May 2015. Instead, it emphasises the involvement of the Polish government in offering help in the regions of origin (and considers this kind of assistance to be the most effective solution). The government has also been working on legal amendments aimed at accelerating asylum proceedings in circumstances when there has been a potential misuse of asylum procedures, such as cases in which the foreigner’s intention was to get into Poland in order to enjoy the possibility of moving freely, although not always lawfully, to countries perceived as more attractive and more supportive for asylum seekers. The direction of proposed changes in law reflects the emphasis placed on internal state security, whereas the developments observed since late 2015 have raised concerns about respect for human rights, particularly in cases of arbitrarily denied or restricted access to asylum procedure and push-backs of potential applicants.

This text is based on the report entitled “Poland – Country Report: Legal and Policy Framework of Migration Governance” (M. Szulecka, M. Pachocka, K. Sobczak-Szelc, Global Migration: Consequences and Responses – Working Paper Series, 14 September 2018, p. 65–66) therefore in order to better understand the socio-economic, political, legal, institutional and policy context of migration governance in Poland, we encourage you to read our full publication which is available within the framework of RESPOND’s Working Paper Series Global Migration: Consequences and Responses.